Manthan

Shyam Benegal, 1976

Runtime: 134 minutes

Language: Hindi, with some English

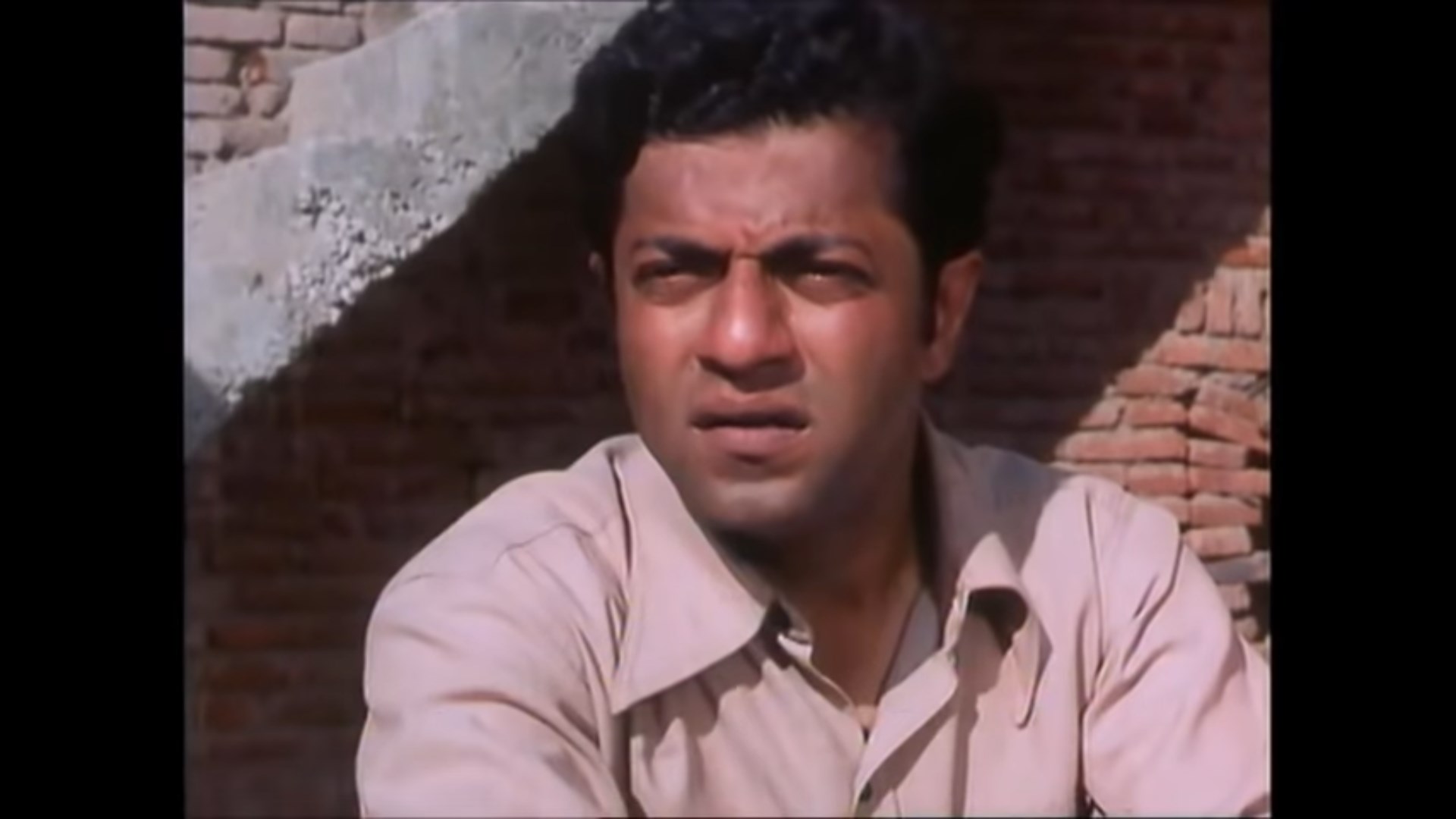

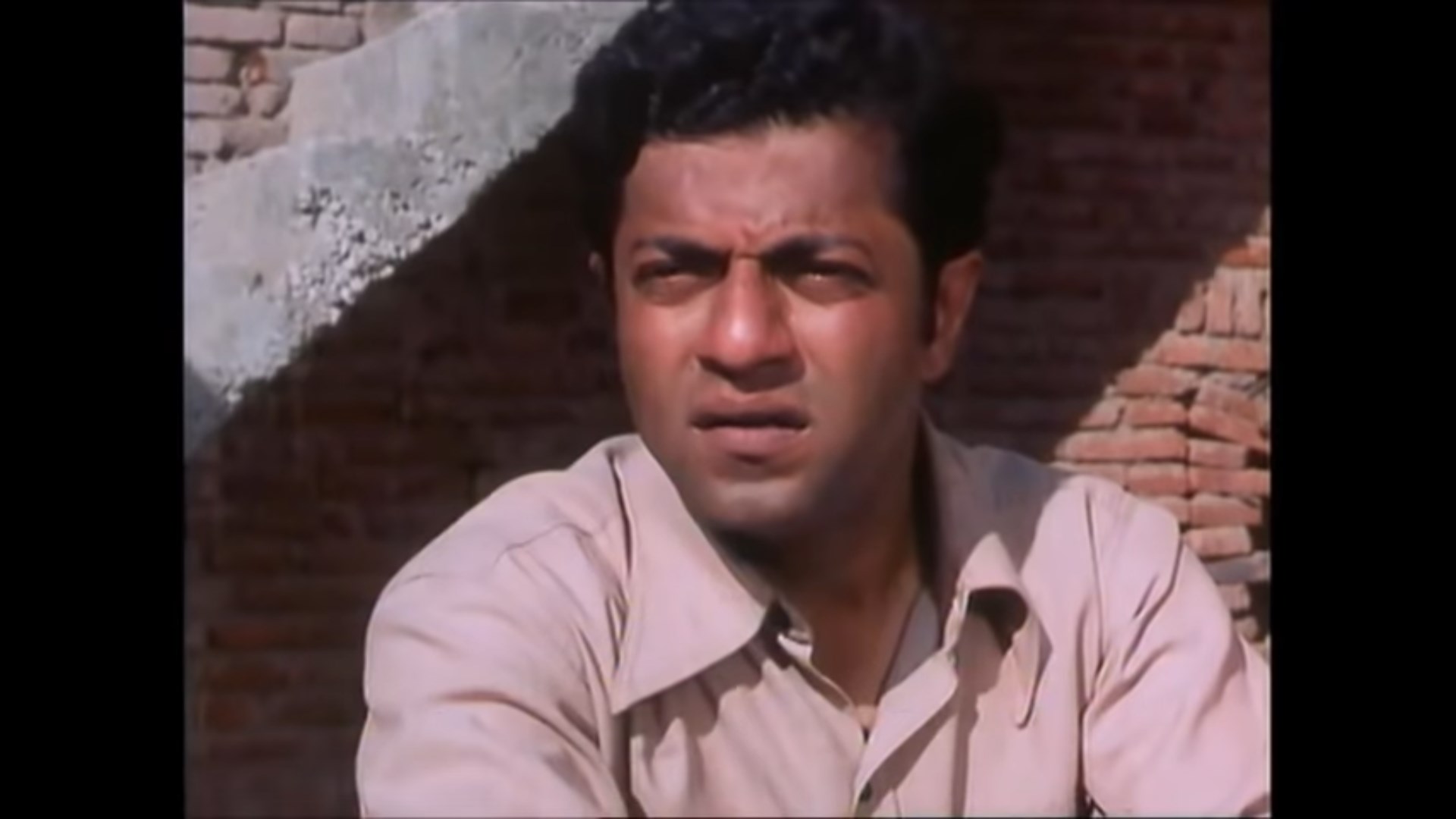

Starring: Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, Naseeruddin Shah, Amrish Puri

Manthan (English: Churning) is a 1976 Hindi film directed by Shyam Benegal, inspired by the pioneering milk cooperative movement of Verghese Kurien, and is written jointly by him and Vijay Tendulkar. It is set amidst the backdrop of the White Revolution of India. Aside from the great measurable success that this project was, it also demonstrated the power of “collective might” as it was entirely crowdfunded by 500,000 farmers who donated Rs. 2 each. The film traces the origins of the movement through its fictionalised narrative, based around rural empowerment, when a young veterinary surgeon, played by Girish Karnad, a character based on the then National Dairy Development Board chief, the 33-year-old Verghese Kurien, who joined hands with local social worker, Tribhovandas Patel, which led to the setting up of a local milk cooperative, in Anand, Gujarat.

Lauren: I got a distinctly Norma Rae vibe from this film – but it’s not a standalone film about labor rights or the power of collective bargaining. And it’s definitely not a film that can be understood out of context from Indian history. It takes place during the “White Revolution” of the 1970s when India was ramping up dairy production (eventually positioning India, decades later, as the number one dairy producer in the world) and shifting the control of production into the hands of Indian dairy farmers.

Gaurav: The first scenes in the film show us just how pessimistic India still is in the aftermath of colonial rule. There’s a lot of distrust of change. The villagers in the film only know one way of thinking, one way of doing things. If the only sky you’ve ever seen is cloudy and gray, it’s difficult to comprehend that it can be blue; that any other shade can exist. That things can be different. I think this inability to believe in change – this struggle between Idealism and Realism, of the “India We Want“ versus the “India We Have“ – is a big theme of Manthan.

“When you get a thought in your brain, is that the only thought that you can understand? The only way that you can think?” Dr. Rao (Girish Karnad) asks this of Bindu (Smita Patil), a strong-minded Dalit woman in the village, when she resists his offer to help. Dr. Rao is a veterinarian and a young idealist who arrives from the city with the intention of helping the dairy farmers form a milk cooperative. The milk cooperative, he tells them, will help them get a fair price for the dairy they produce. It will build a system where there’s funding available for roads, schools, and even the cost of caring for their cattle.

But the villagers regard him with skepticism. They don’t want change. They’re comfortable with how things are, even if it might be harming them.

This feels like a legacy of colonialism. This idea of we do things a certain way, this is our way, do not question it, do not challenge it, don’t rock the boat. Change is what risks disrupting the equilibrium. Aren’t things working? Why would you come in and upset the “natural” order of things?

Dr. Rao – moreover, the concept of the milk cooperative itself – introduces revolution. The villagers view revolution as dangerous because it moves them outside of their comfort zone. The community leaders and wealthy dairy buyers see all of this as a threat because the milk cooperative is giving ideas, power and agency to people who don’t normally have those things. Long ago they did, before colonial rule. But it’s been so long that they’ve gotten used to the way things are. Living under the heel of Mishra Ji (Amrish Puri), the local businessman and ostensible diary lord. Mishra Ji sets the prices. He influences local politics, buys votes, and buys their love.

Lauren: Am I understanding you correctly that you’re saying the reason that many people in post-colonial India are resistant to change is because they saw their world steamrolled by colonial rule and oppression?

Gaurav: This may be too reductive, but I think of it a bit like an abusive relationship. Indians living in the shadow of colonial rule are accustomed to a certain kind of abusive power and authority being lorded over them. And it’s hard to break free from that. Does that make sense?

Lauren: I don’t think that’s reductive. It just gets to the essence of the relationship. It’s a sick system. Colonialism is a sick system. Abusive relationships are sick systems. In a sick system, you’re so exhausted that you become comfortable with what you’re familiar, even if it’s not healthy for you. Even if it’s not what you truly want. You just begin to think you want it, because your abuser has convinced you that you need them – and their guidance, or whatever artifact of that guidance – to keep you on the straight and narrow.

Gaurav: Let’s go back to Dr. Rao’s first interactions with the villages – in particular, Bindu.

Right away there’s a sense of distrust. You don’t belong here. Who are you? What do you want? Why should I give you the milk I’ve worked hard to farm? There’s an “us” versus “them” division, discord, disharmony.

What are your thoughts on that first sequence with Dr. Rao asking Bindu for a sample of her cattle’s milk so that he can analyze the fat content?

Lauren: The moment she sees him she doesn’t trust him. He’s an outsider from the city. She thinks he’s there from the government to tell her to stop having kids. “The Have-Less Children People Already Came and Went!” she shouts. She’s someone who doesn’t have any fucks left to give when it comes to authority.

I especially loved how when he asked Bindu, “Where is this child’s father?” she shouts, “His father is right here!” She’s talking about herself. We don’t see a man around. (Her husband becomes an issue later.) Our introduction to Bindu is an independent woman who runs her home like a business and on her own terms. She hasn’t quite realized yet how much she may be losing because her community continues to kowtow to the dairy lords lowballing them on the price of milk.

Gaurav: I also appreciate her no fucks left to give attitude. She’s bold, honest, and confrontational.

Continue reading “Manthan (1976)” →